For what I hope are obvious reasons, this post also appears on my Friends of Charles Darwin website.

Like many prolific authors, Charles Darwin did not enjoy writing books, claiming it was ‘dull work, but must be borne’1. He was easily distracted from his writing, preferring to spend his time observing, experimenting and hypothesising. But books needed to be written, and, over the years, Darwin adopted a writing process that worked for him. Indeed, certain elements of his process are still advocated as best practice by many modern writers.

Darwin’s approach to book-writing, described in detail in the Reminiscences 2 of his son Francis, and in less detail in Darwin’s Autobiography 3, went through four key stages:

- Top-down planning/outlining

- Initial rough draft

- Fair copies

- Revision of printers’ proofs

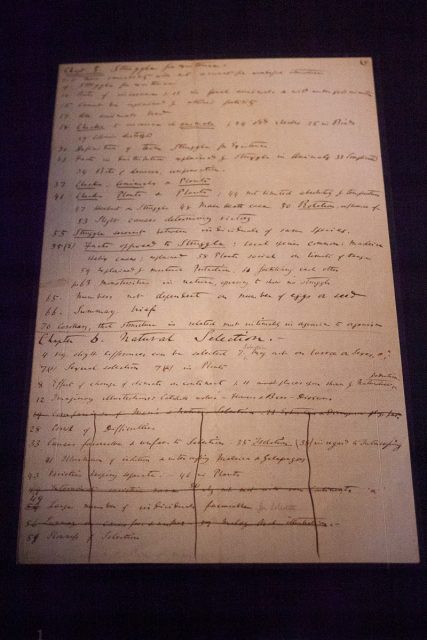

Top-down planning/outlining

When beginning his major works, Darwin would make a rough outline of the whole book first, then drill down into more detail:

[W]ith my large books I spend a good deal of time over the general arrangement of the matter. I first make the rudest outline in two or three pages, and then a larger one in several pages, a few words or one word standing for a whole discussion or series of facts. Each one of these headings is again enlarged and often transferred before I begin to write in extenso.4

Photo: Richard Carter

As described in my article about Darwin’s note-making system, while he was carrying out research, Darwin collected loose slips of information in different portfolios dedicated to particular topics of interest. The idea was, once he came to start writing on a particular topic, he would be able to open the corresponding portfolio, shuffle the various loose slips of paper around, and come up with a detailed outline. From this outline, he would develop an initial rough draft.

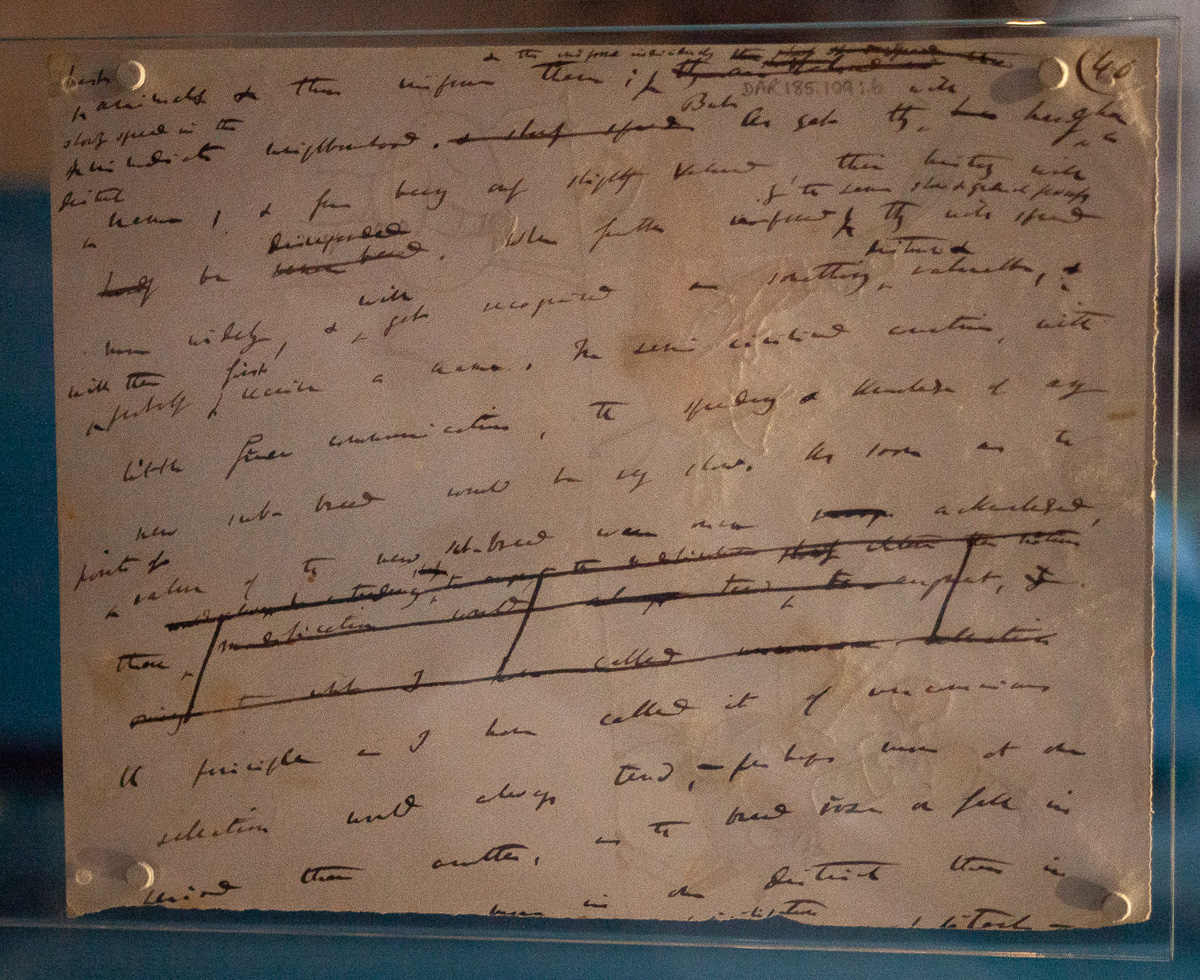

Initial rough draft

In his early days as a writer, Darwin struggled with his first drafts. He fussed too much over wording, trying to make the draft as good as possible. In later years he overcame this difficulty by adopting an approach recommended by many modern writers of simply going with the flow, not worrying at all about quality, and getting any old crap down on paper as quickly as possible:

There seems to be a sort of fatality in my mind leading me to put at first my statement or proposition in a wrong or awkward form. Formerly I used to think about my sentences before writing them down; but for several years I have found that it saves time to scribble in a vile hand whole pages as quickly as I possibly can, contracting half the words; and then correct deliberately. Sentences thus scribbled down are often better ones than I could have written deliberately.5

Photo: Richard Carter

One trick the proudly thrifty Darwin adopted to avoid both the terror of the blank page, and worrying too much about style in the rough drafts was to write on the backs of old letters and manuscripts.

He had a pet economy in paper, but it was rather a hobby than a real economy. All the blank sheets of letters received were kept in a portfolio to be used in making notes; it was his respect for paper that made him write so much on the backs of his old MS., and in this way, unfortunately, he destroyed large parts of the original MS. of his books. […]

It was characteristic of him that he felt unable to write with sufficient want of care if he used his best paper[.]6

Photo: Richard Carter

Fair copies

Having completed his rough draft, Darwin would have a fair copy made on widely ruled paper. So bad was his handwriting that he outsourced the production of this fair copy to the local schoolmaster, Mr Norman.

My father became so used to Mr. Norman’s handwriting, that he could not correct manuscript, even when clearly written out by one of his children, until it had been recopied by Mr. Norman.7

Darwin would then correct and improve this fair copy, and have a second, final fair copy made for sending to the printer.

One side-benefit Darwin saw in making two different fair copies was that the first, subsequently amended, fair copy could serve as a reassuring backup of his work, should something happen to the second copy after it was dispatched to the printer.

Revision of printers’ proofs

Once the proofs came back from the printer, Darwin set to work correcting and improving his words. He did not at all enjoy this stage of the writing process.

It was at this stage that he first seriously considered the style of what he had written. When this was going on he usually started some other piece of work as a relief. The correction of slips consisted in fact of two processes, for the corrections were first written in pencil, and then re-considered and written in ink.8

It sounds strange to modern readers that Darwin would only start worrying about literary style after the printers had already produced proofs of his work. Working on my own books, I find it extremely beneficial to be able to read my drafts in a different medium to the computer-screen on which they were composed—either on paper or e-book reader. Darwin also seems to have appreciated seeing his own words in a different format:

I never can write decently till I see it in print.9

In terms of literary style, Darwin preferred simple language with few superfluous words. When his new friend Henry Walter Bates began work on his first book, Darwin offered some stylistic advice:

As an old hackneyed author let me give you a bit of advice, viz to strike out every word, which is not quite necessary to connect subjects & which would not interest a stranger. I constantly asked myself, would a stranger care for this? & struck out or left in accordingly.— I think too much pains cannot be taken in making style transparently clear & throwing eloquence to the dogs. I hope that you will not think these few words impertinent.—10

During this final stage of the writing process, Darwin welcomed corrections and suggestions from family members. According to his daughter Henrietta11, he was always extremely grateful for suggested changes, making a point of remarking how much they improved the text, or giving all sorts of reasons why he didn’t agree with the proposed changes.

Darwin would then read his corrected proofs out loud to determine whether they needed further amendment:

I find it good to correct in pencil & read aloud, & if it sounds well, not to plague more over it.12

He would then return the completed book to the printer:

[I]t is great satisfaction finishing a job. It is certainly the greatest pleasure about a book.13

At which point, no doubt relieved to have got another book out of the way, Darwin would immediately move on to his next project.

…Which reminds me, I really ought to be working on my next book, rather than banging out posts on my website.

- Darwin, C.R. to H. W. Bates, 18 October [1862]. Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 3773”. [Read online] ↩︎

- Darwin, F. (ed.) (1887). The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter. London: John Murray. [Read online] ↩︎

- Darwin, C. R. (1958). The Autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809-1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his grand-daughter Nora Barlow. Collins. [Read online] ↩︎

- Darwin, C.R. 1958 ↩︎

- Darwin, C.R. 1958 ↩︎

- Darwin, F. 1887 ↩︎

- Darwin, F. 1887 ↩︎

- Darwin, F. 1887 ↩︎

- Darwin, C.R. to J. D. Hooker, 30 May [1861]. Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 3168”. [Read online] ↩︎

- Darwin, C.R. to H. W. Bates, 25 September [1861]. Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 3266”. [Read online] ↩︎

- Darwin, F. 1887 ↩︎

- DCP Letter no. 3773 ↩︎

- Darwin, C.R. to J. D. Hooker, [21 December 1862]. Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 3871”. [Read online] ↩︎

Leave a Reply