Some time back in the late twentieth century, I wrote to the good people at the Oxford English Dictionary to complain about a blatant inconsistency: my copy of their magisterial work contained the Scots dialect word thole (meaning to bear or tolerate), but not the equivalent Yorkshire dialect word, thoil. In their reply, the OED politely explained words only earn a place in their dictionary if they appear in certain recognised written sources. I guess we have Robbie Burns to thank/blame for all the obscure Scots words in there. Presumably, there must be few recognised written Yorkshire-dialect sources.

In On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin drew an analogy between the evolution of species and the evolution of languages, pointing out he expected a future family-tree of languages would echo the genealogical relationships of the various human sub-populations around the world that spoke them:

If we possessed a perfect pedigree of mankind, a genealogical arrangement of the races of man would afford the best classification of the various languages now spoken throughout the world; and if all extinct languages, and all intermediate and slowly changing dialects, had to be included, such an arrangement would, I think, be the only possible one.

Clearly, individual languages being cultural artefacts, rather than biological ones—people inherit an ability to speak, not an ability to speak a particular language—things are a bit more complicated than Darwin made out. But the analogy between biological evolution and language evolution is an interesting one. At what point do different local varieties of a species diverge enough to become separate species? And at what point do two local dialects of a language diverge enough to become different languages? Darwin often stressed the difference between varieties and species was moot, being simply a difference of degree. The same could be said of dialects and languages.

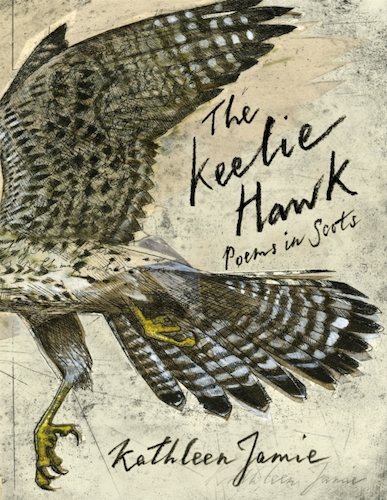

In the afterword to her poetry collection, The Keelie Hawk, Kathleen Jamie makes it clear she thinks Scots should be classified as a language in its own right, rather than a dialect of English. That’s fine by me—although it does raise the question of whether all those Burnsian words like thole belong in the OED at all. Either way, Scots and English are clearly closely related, being separated to a lesser degree from each other than from many other languages. The Scottish thole, the Yorkshire thoil, and the English word tolerate share a recent common ancestry. They also share a common ancestry with similar words in other Indo-European languages, including Old English, Proto-Germanic, Old High German, Old Norse, and Gothic. As with species, the relationships between languages are best analysed through the similarities of their traits.

…None of which is getting this book reviewed!

The Keelie Hawk (Scots for The Kestrel) is a collection of poems written in Scots with accompanying prose-poem English translations by the author.

Kathleen Jamie is my favourite writer. I would happily read her shopping lists. She’s even managed to get me to read—and enjoy—poetry. But I have to admit my eyes tend to glaze over when she slips in more than the odd word of Scots. This is in no way intended as a criticism—Jamie is entitled to use whatever words (or language) she damn well pleases; when she chooses to write, as she does in this book, in pure Scots, fat English monoglots are probably not her target audience.

That said, I did very much enjoy Jamie’s English translations of her own words, which encouraged me to try to appreciate the sound and rhythm of the Scots more than I would normally. The themes of the poems will be familiar to anyone who has read her earlier work.

As with all of Kathleen Jamie’s books, I highly recommend The Keelie Hawk—especially, but not only, if you happen to speak Scots.

- Buy this book from Bookshop.org (UK) and help tax-paying, independent bookshops.

- Buy this book from Amazon.co.uk

- Buy this book from Amazon.com

Leave a Reply