Jen and I recently spent a few days in Bradford, the 2025 UK Capital of Culture. We took the opportunity to attend our first ever opera, at the wonderful St George’s Hall. I’m glad we went, but I’ve scratched that particular cultural itch now. Call me a Philistine, but I’m an honest Philistine: opera is not my cup of tea. I gave it a shot, didn’t I?

While in town, we also took in two exhibitions celebrating the work of veteran Bradford-born artist David Hockney. I’ve long admired Hockney for his continuing willingness to experiment with new media. Examples on display in Bradford included artwork produced on his iPad, ‘joiner’ photo-collages, and video collages.

The four video collages depicted a slow journey through Woldgate Woods in East Yorkshire in each of the four seasons. I’d enjoyed the snowy winter footage before, at an earlier exhibition in nearby Salt’s Mill, so it was a treat to see all four collages together. The videos were taken using nine cameras attached to the front of a car, each recording a different segment of a 3 x 3-screen moving collage. As it was physically impossible for the cameras to capture their recordings from exactly the same viewpoint, the resulting individual segments didn’t quite join up seamlessly, lending a disconcertingly three-dimensional feel to the collage. We perceive depth by looking at the world from two slightly different viewpoints: our two eyes. This was like having your eyes turned up to nine. The effect was mesmerising. Here’s a short video I recorded of the winter collage last year at Salt’s Mill:

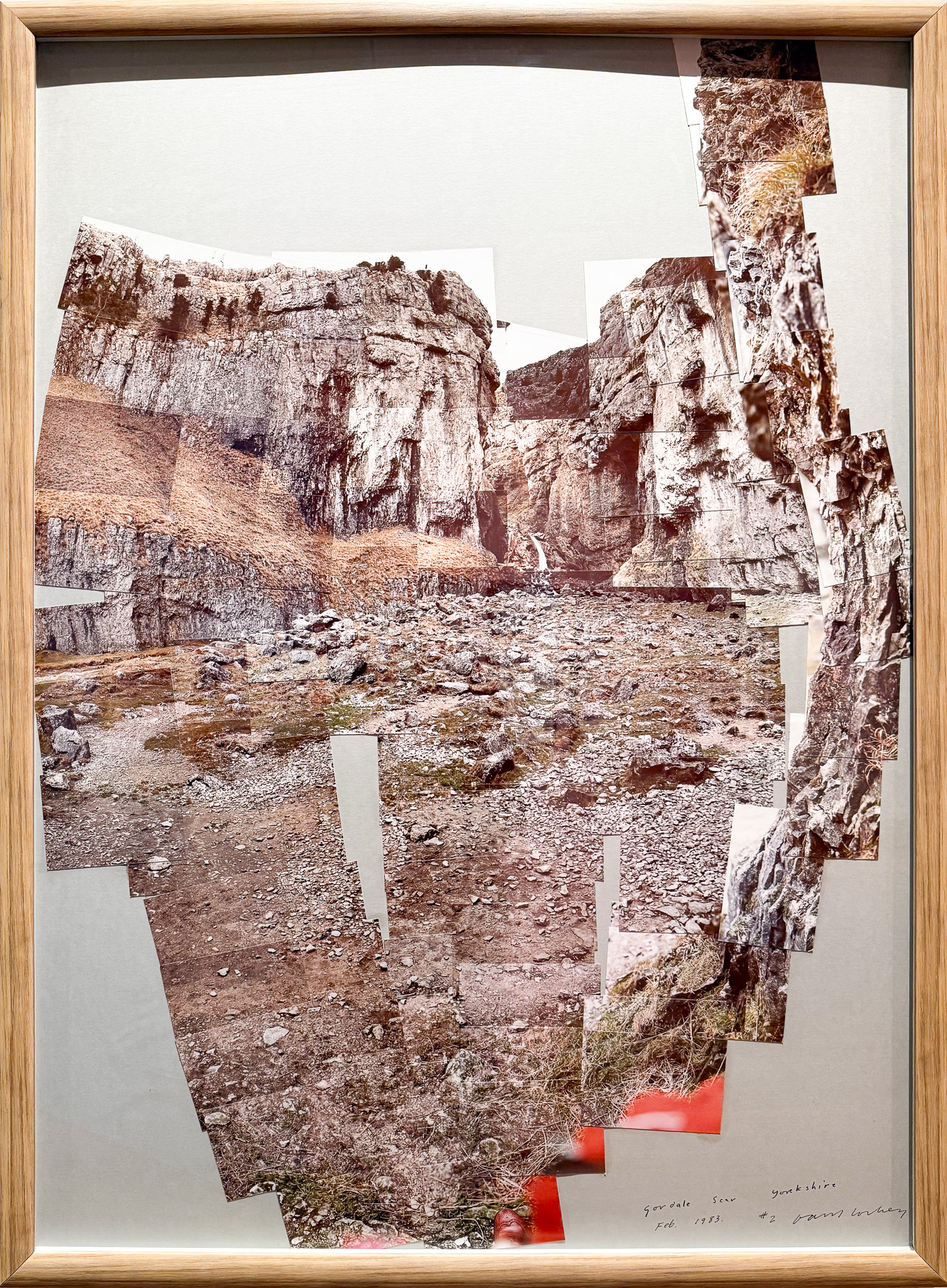

Also on show in Bradford were a number of Hockney’s ‘joiner’ photographic images: collages of views assembled from hundreds of photos taken of individual details within the view. Again, I’d seen such images at earlier Hockney exhibitions, and a framed poster of one graces our living room wall. As a keen amateur photographer, it delights me that one of our most celebrated artists is prepared to experiment with what are, in effect, snapshots—the most popular and, I would argue, most important form of visual expression. As with the video images, but more so, these photographic ‘joiners’ are fragmented images which, despite the name, don’t quite join up. Viewing these images is like having your eyes turned up to several hundred. The almost pixelated result is spellbinding: you find yourself examining individual photos in detail, then zooming out again to see the bigger picture—examining the wood and the trees, so to speak.

Although the still images could all, in theory, have been taken from exactly the same viewpoint, like the video collages, they clearly weren’t. Unlike with the video collages, the joiner images were all captured with a single camera, which meant each of them was taken at a slightly different time. This sometimes added a temporal element to the resulting collage. In one of the joiners made in 1985, which depicted the outside of a former incarnation of the very building we were in, the same young woman was captured five or six times as she crossed the road and made her way up a side-street: the passage of time captured in a still image.

One of my favourite joiner images was made at Gordale Scar in the Yorkshire Dales—a place I’ve visited and photographed many times. While I was examining individual photos of small clusters of pebbles in this work, it finally dawned on me what these images remind me of: Hockney’s joiners, assembled from scores of smaller images, resemble the panoramic pictures beamed back to Earth by robots exploring the surface of Mars. And, just as parts of the Martian rovers themselves often appear in the bottom of the Nasa images, Hockney’s own feet appeared in the bottom of his Gordale joiner.

Despite many visits to Gordale over the years, I’ve never explored it in the level of detail Hockney has. His joiner images are a lesson in what it‘s like to pay close attention.

Leave a Reply